In this series of posts I have been greatly aided by Lincoln Mullen, assistant professor at George Mason University and a frequent collaborator with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media there. You can find additional information on this post, including all the coding where we “show our work,” at its associated RPub.

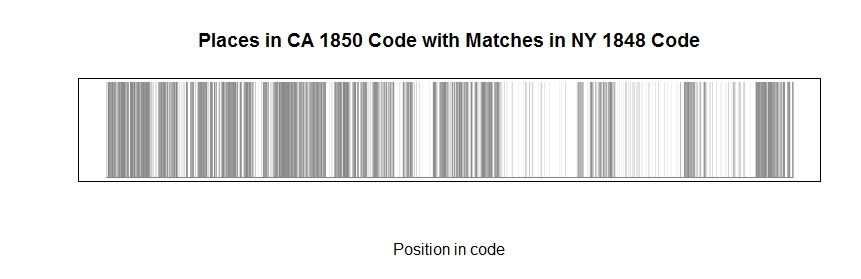

Since my last post, I’ve pulled together about thirty more codes, OCR’d them, and cleaned up the resulting text for comparison. This larger sample size allows for more sophisticated comparison than the one-off density plots, but the basic computation remains the same. With the density plot experiment, we asked “how much of the text in X code matches the text in Y code, and where are are those matches distributed in X code?”

Now instead of comparing one jurisdiction with another single jurisdiction, we can compare all codes to each other all at once and and graph the percentage of matching n-grams between each code: Continue reading