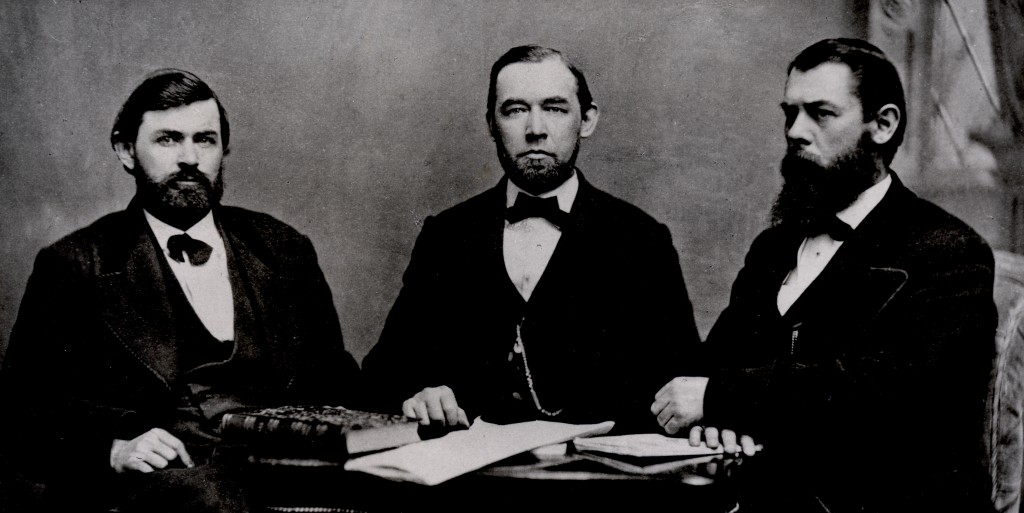

David Dudley Field has often been depicted as lone genius. That image served a political purpose when the architects of federal procedure sought to cast Field as a prophetic voice crying in a wilderness of antimodern practice. See especially Charles E. Clark, Address on the Proposed Rules of Civil Procedure, American Bar Association Journal, 22 (1936):787 (“Nevertheless, even Field was a lone worker, who carried through, by sheer force of his own intellectual strength, changes at best only half-heartedly supported, and often opposed even after their adoption, by his colleagues of the bench and bar.”). On the contrary, Field was joined by a host of what political science literature calls “policy entrepreneurs”—official and unofficial agents who frame political problems and propose, lobby, and advertise for the legislative “solutions” to those problems. See Luc Bernier and Taieb Hafsi, “The Changing Nature of Public Entrepreneurship,” Public Administration Review, 67 (2007):488-503; Michael Mintrom, “Policy Entrepreneurs and the Diffusion of Innovation,” American Journal of Political Science, 41 (1997):738-70.

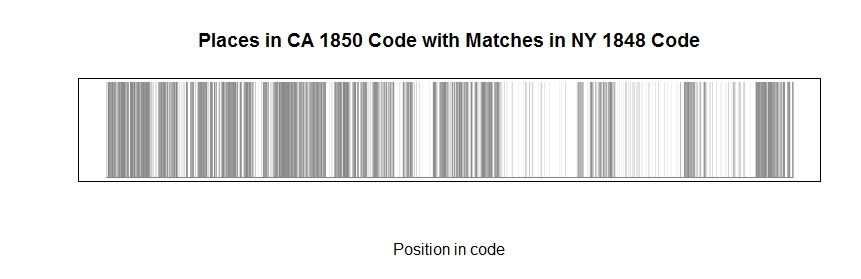

The following work-in-progress tracks the many code commissions and legislative advocates of codification during the Field Code era. Nineteenth-century legal historians often focusing on sparring with Morton Horwitz over the elite, “orthodox” defenders of the common law. See Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law: The Crisis of Legal Orthodoxy (Oxford 1994); Kunal Parker, Common Law, History, and Democracy in America (Cambridge 2011); David Rabban, Law’s History: American Legal Thought and the Trans-Atlantic Turn to History (Cambridge 2013). But as yet we know far too little about the equally elite supposedly “heterodox” advocates of codification and reform. This list provides a place to start.

Continue reading →